Yesterday, Elon Musk got on stage at the 2016 International Astronautical Congress and unveiled the first real details about the big fucking rocket they’re making.

A couple months ago, when SpaceX first announced that this would be happening in late September, it hit me that I might still have special privileges with them, kind of grandfathered in from my time working with Elon and his companies in 2015 (which resulted in an in-depth four-part blog series). So I reached out and asked if I could learn about the big fucking rocket ahead of time and write a post about it.

They said yes.

A little while later, I got on a call with Elon to discuss the rocket, the timeline, and the big plan this was all a part of. We started off how we always do.

Then I brought up the rocket.

Eventually, we were able to settle in to a fascinating conversation about this insane machine SpaceX is building and what’s going to happen with it.

Now, before we get into things—

This post is only a piece of The SpaceX Story—one of the most amazing stories of our time—and a story I spent three months and 40,000 words telling last year. If you really want to understand this and you haven’t read that post yet, I recommend you start there. The post has three parts, divided into five pages:

Part 1: The Story of Humans and Space

Part 3: How to Colonize Mars

→ Phase 1: Figure out how to put things into space

→ Phase 2: Revolutionize the cost of space travel

→ Phase 3: Colonize Mars

For those who have read the post and want a refresher or those who just want to hear about the big fucking rocket and move on with their day, here’s a quick overview of the background:

The Context

To understand why the big fucking rocket matters, you have to understand this sentence:

SpaceX is trying to make human life multi-planetary by building a self-sustaining, one-million-person civilization on Mars.

Let’s go part by part.

Why make human life multi-planetary?

Two reasons:

1) It’s fun and exciting. (Here’s a clip from one of the interviews I did with Elon last year where he articulates this point.)

2) It’s not a great idea to have all of our eggs in one basket. Right now we’re all on Earth, which means that if something terrible happens on Earth—caused by nature or by our own technology—we’re done. That’s like having a precious digital photo album saved only on one not-necessarily-reliable hard drive. If you were in that situation, you’d be smart to back the album up on a second hard drive. That’s the idea here. Elon calls it “life insurance for the species.”

Why Mars?

Venus is a dick, with its lead-melting temperatures, its crushing atmospheric pressure, and its unbearable winds.

The moon has few natural resources, a 29-day day, and with no atmosphere to either provide protection against the sun during the day or warm things up at night, both day and night become murderous. Same deal on Mercury.

Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune are just huge balls of gas pretending to be planets.

Certain moons of Jupiter and Saturn are possibly habitable, but they’re farther away and colder and darker than Mars, so why would we do that.

Pluto is even farther and colder and darker. Stop asking me about Pluto.

That leaves Mars. Mars isn’t a good time. If Mars were a place on Earth, it’s somewhere no one would want to go. But compared to all of those other options, it’s a dream. It’s cold but not that cold. It’s kind of dark but not that much darker than Earth. It’s far but not that far. Its day is almost the same length as ours, which is nice for us and hugely helpful for growing Earthly vegetation. Its surface gravity isn’t crazy low or crazy high (it’s around a third of Earth’s). It has a ton of (frozen) water and a decent amount of CO2, which are critical for early attempts at living there and hugely helpful for future attempts to “terraform” the planet into a place more livable for humans. All things considered, we’re very lucky to have an option as good as Mars—in most other solar systems, we probably wouldn’t.

Why 1,000,000 people?

Because Elon thinks that’s a rough estimate for the number of people you’d need to have on Mars in order for the Mars civilization to be “self-sustaining”—with self-sustaining defined by Elon as: “Even if the spaceships from Earth permanently stop coming, the colony doesn’t eventually die out—which requires a huge industrial base, and a much harder industrial base to create than being on Earth.”

In other words, if hard drive #2 relies on hard drive #1 in order to stay working, then your photo album isn’t really backed up, is it? The whole point of hard drive #2 is to save the day if hard drive #1 permanently crashes.

And while the Earth hard drive could “crash” for many exciting reasons—an asteroid hits us, AI kills us, Trump kills us, ISIS creates some upsetting biological weapon, etc.—Elon also warns about the less dramatic possibility that the Earth ships stop coming simply because Earth civilization stops having the capability to send them:

The spaceships from Earth could stop coming for other reasons—it could be WWIII, it could be that Earth becomes a religious state, it could be some gradual decline where Earth civilization just sinks under its own weight. At one point the Egyptians were able to build pyramids, and then they forgot how to do that. And then they forgot how to read hieroglyphics, until the Rosetta Stone. Rome as well—they had indoor plumbing, they had advanced aqueducts, and then that fell apart. China at one point had the world’s biggest fleet of sailing ships and they were sailing as far as Africa, then some crazy emperor came along and decided that was bad and had them all burnt. So you just don’t know what’s gonna happen. The key threshold to pass is the number of people and tons of cargo required to make things self-sustaining. And that’s probably something like a million people and probably something like 10-100 million tons of cargo.

In other words, let’s not wait on this.

Great, but how the hell do you bring 1,000,000 people to Mars?

You make this green part exist:

It’s kind of simple. If we get to a point where there are a million people on Earth who both want to go to Mars and can afford to go to Mars, there will be a million people on Mars.

Unfortunately, right now the yellow circle is tiny and the blue circle doesn’t exist.

Elon thinks—and I kind of do too—that if the blue circle can get big enough, the yellow circle will take care of itself. If Mars is affordable and safe and you know you’ll be able to come back, a lot of people will want to go.

The hard part is the blue circle. Here’s the issue:

Last time the US Congress checked with NASA, the cost to send a five-person crew to Mars was $50 billion. $10 billion a person. Elon thinks that to make the blue circle sufficiently large, it needs to cost $500,000 a person. 1/20,000 of the current cost.

1/20,000.

That’s like looking at the car industry and saying, “Right now a new Honda costs around $20,000. To make this a viable industry, we need to get the cost of a new car down to $1.”

So what the hell?

Here’s the hell:

Imagine if the way planes worked was that they took off, flew to their destination, but then instead of landing, all the passengers parachuted down to the ground and then the plane landed by smashing into the ocean and blowing up. So every plane flew exactly once, and to have a new flight happen, you’d have to build another plane.

A plane ticket would cost $1.5 million.

Space travel is currently so expensive mostly because we land rockets by crashing them into the ocean (or incinerating them in the atmosphere).

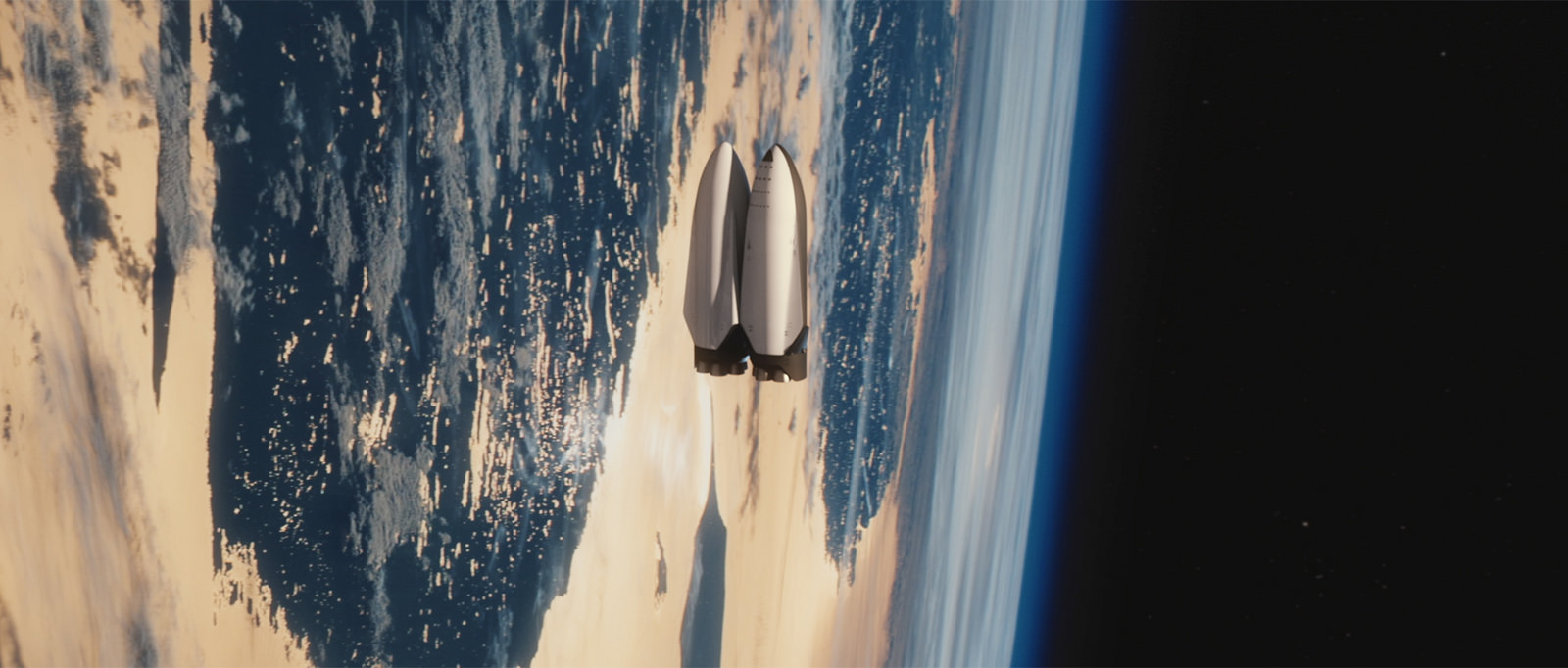

When Elon started SpaceX, he was determined to fix this problem. It was a tall order, given that no one had ever done it before—including nations like the US and Russia who had spent billions trying. But SpaceX puzzled away at the problem year after year, and after trying and failing a bunch of times, in late 2015, they nailed it:

Then they nailed it again. And again. And again. Now they nail it more often than not. Here’s a daytime view of a recent landing:

Soon, for the first time, a previously used-and-landed, flight-tested Falcon 9 will carry out a new mission for SpaceX, officially making SpaceX rockets “reusable.”

To fly a mission on a used rocket, you only need to pay for propellant (fuel and liquid oxygen) and a bit of routine maintenance. This cuts the price of space travel down by 100 or even 1,000 times.

That leaves us with somewhere between 19/20 and 199/200 of the cost left to cut. Part of that will happen when SpaceX takes 100 or more people to Mars at a time, instead of five (the number Congress asked NASA about). The rest of it is taken care of by a few simple innovations, like refueling the spaceships in orbit (which lowers the cost by 5-10x) and manufacturing propellant on Mars so you don’t have to carry your return propellant with you (which lowers the cost by another 5-10x). More on those things later.

Suddenly, not only can the price get down to $500,000/ticket, it can probably go even lower (Elon thinks it could eventually cost under $100,000/person). You may not have noticed it yet, but SpaceX’s innovations are in the process of creating a total revolution in the cost of space travel—a change that will open doors we can’t imagine being open today. And when that revolution goes far enough, SpaceX’s vision of putting 1,000,000 people on Mars really—actually—seriously—may happen.

We’re going to Mars. And this week, SpaceX showed us the thing that’s gonna take us there.

The Rocket

“It’s so mind-blowing. It blows my mind, and I see it every week.”

Elon’s pumped. And when you learn about the big fucking rocket he’s building, you’ll understand why.

First, let’s absorb the challenge at hand. It’s often said that space is hard. To this day, only a few hundred people have been in space, only a few countries have the ability to launch something into space, and the history of human space travel is littered with tragic launch failures. Firing something super heavy and delicate and full of explosive liquid up through the atmosphere without anything going wrong is incredibly hard.

But when we talk about humans going into space, we’re talking mostly about humans going into Low Earth Orbit, a layer of space between 100 and 1,200 miles above the ground—and normally, they’re headed only 250 miles up to the International Space Station. The only time humans have gone farther were the small handful of Americans who made it out to the moon in the 1960s, traveling about 250,000 miles away.

When Earth and Mars are at their closest, Mars is somewhere between 34 and 60 million miles away—about 200 times farther away than the moon and about 200,000 times farther away than the ISS.

The moon is just over one light second away.

Mars is more than three light minutes away.

Mars is far.

Elon likes to compare the Earth-to-Mars trip to crossing the Atlantic Ocean, noting that using that scale, going to the moon would only be crossing the English Channel (and going to the ISS would be going to a dock 117 feet off the shore). Continuing with that comparison, he says, “A rocket made to go to Low Earth Orbit or even the moon is basically like a coastal fishing vessel, compared to a colonial transport system that is trying to go 1,000 times further.”

On top of that, it might be worth it to take only a few humans or a single satellite up into Low Earth Orbit—but if you’re going all the way to Mars, you want to take a lot more than that. So you have to take much more mass, much further. Multiplying the distance factor by the payload factor, Elon explains that a Mars transport system “is like literally a million times more capable than what the current world launch system can do. It has to be.”

It also has to be incredibly advanced. Elon says, “It’s not just bigger, it needs to be more efficient. There’s a false dichotomy when it comes to rockets of ‘small and complex’ or ‘big and dumb.’ People talk about the ‘big dumb booster’—that won’t work. You need a big smart booster. If you want to build a Mars colony, you have no choice— you have to make it big and efficient.”

So that’s all you have to do—build a rocket that’s a million times more capable than today’s best rockets but who’s also efficient and smart and great in bed.

SpaceX is building it. Meet the Big Fucking Rocket.1

Hard to quite understand the bigness from that picture. So let’s add in some scale:

Or how about this?

It would barely fit diagonally across a football field without going into the stands.

There’s also this:

It’s a skyscraper. Or as Elon puts it, “by far the biggest flying object ever.”

In yesterday’s presentation, Elon explained that this isn’t a first crack at how it might look, or an artist’s impression of how it might look—it’s how it’s going to look. This is the thing they’re building.

Unfortunately, SpaceX seems to be going through an existential crisis when it comes to naming this thing—first it was the Mars Colonial Transporter, then (because it can go way past Mars) it was renamed the Interplanetary Transport System, then yesterday in the presentation, Elon said they haven’t actually settled on a name yet but that the specific spaceship that makes the maiden voyage to Mars might be called Heart of Gold1—so no one knows what to call it.

Which is why—until I hear otherwise—I’ll be calling it something I once heard Elon describe it as in an interview: the Big Fucking Rocket (BFR).

The Big Fucking Rocket is fucking big. At 400 feet tall, it’s the height of a 40-story skyscraper. At 40 feet in diameter, a school bus could fit entirely underneath its footprint. It’s more than three times the mass and generates over three times the thrust of the gargantuan Saturn V—the rocket used in the Apollo mission—which currently stands as by far the biggest rocket humanity has made.

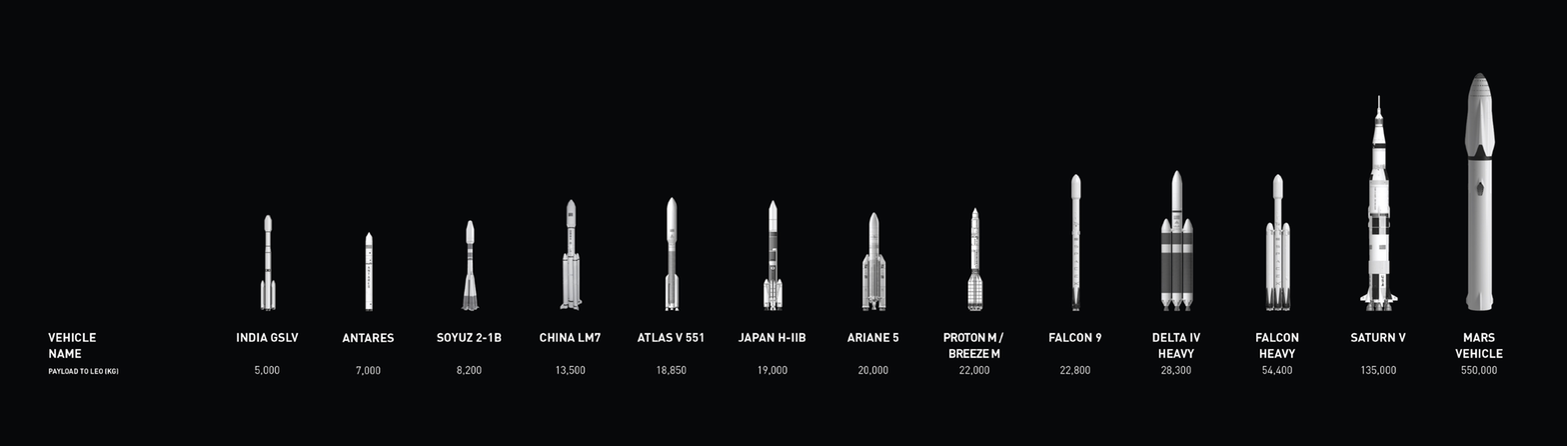

Here’s how it stacks up next to a bunch of other rockets in size:

The difference is even more extreme when you compare the rockets by how many kilograms of payload (i.e. cargo and/or people) they can each take to orbit:

For comparison, SpaceX’s badass Falcon 9 rocket will be able to take about 4 tons of payload to Mars, and the Falcon Heavy—which is about to be today’s most powerful rocket—will be able to take about 13 tons to Mars. Elon believes the BFR will be able to take a few hundred tons of payload to Mars at first and eventually be able to take 1,000 tons. The absurdity of that statistic—that the behemoth Falcon Heavy can only manage a little over 1% of the BFR’s ultimate Mars payload—is pretty hard to absorb.

Now, to be clear—what I’ve been calling the Big Fucking Rocket this whole time is actually two things: a Big Fucking Spaceship sitting on top of a Big Fucking Booster.

The Big Fucking Booster

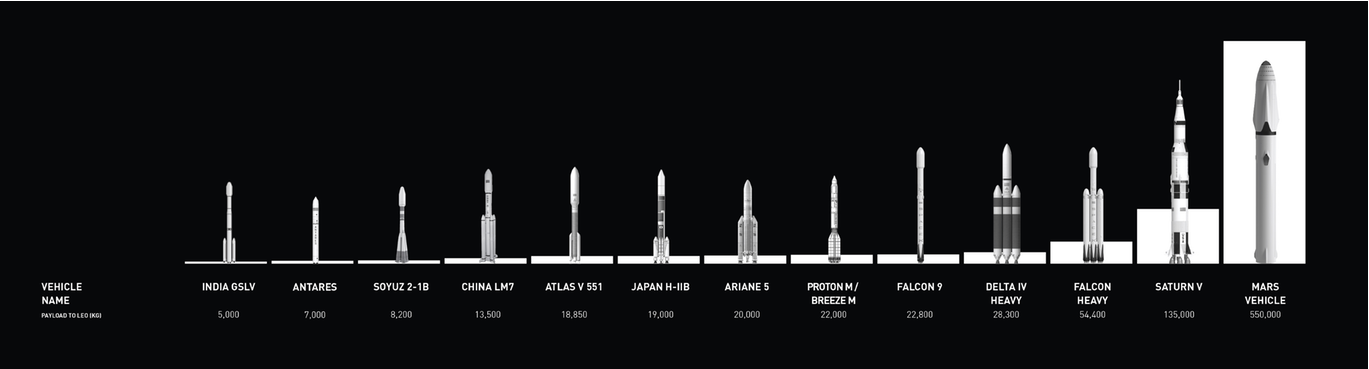

Let’s start by talking about the booster. The 25-story-high booster—AKA the actual rocket of the BFR—is what Elon calls “quite a beast.” It’s the biggest booster of all time—by far. By physical size, definitely, but even more so by thrust.

In the SpaceX post, I talked about the Falcon 9’s nine Merlin engines, and how each one was powerful enough to lift a stack of 40 cars up into the sky—in total, that meant the Falcon 9 set of engines could lift 360 cars. The Falcon Heavy, with its 27 Merlin engines, could lift a stack of over 1,000 cars up past the clouds.2

The Big Fucking Booster sits atop a different kind of engine: the Raptor.

The Raptor engine looks a lot like a Merlin, with one key difference—by significantly increasing the pressure, SpaceX has made the Raptor over three times more powerful than a Merlin.

A single Raptor engine produces 310 tons of thrust—enough to lift 310 tons, or a stack of 172 cars, or an entire Boeing 747 airplane, into the sky. That’s what one Raptor can do.3

And the BFB has 42 of them.4

All together, that’s an unheard of 13,033 tons of thrust, enough to push more than 7,000 cars—or 50 large airplanes—up to space.

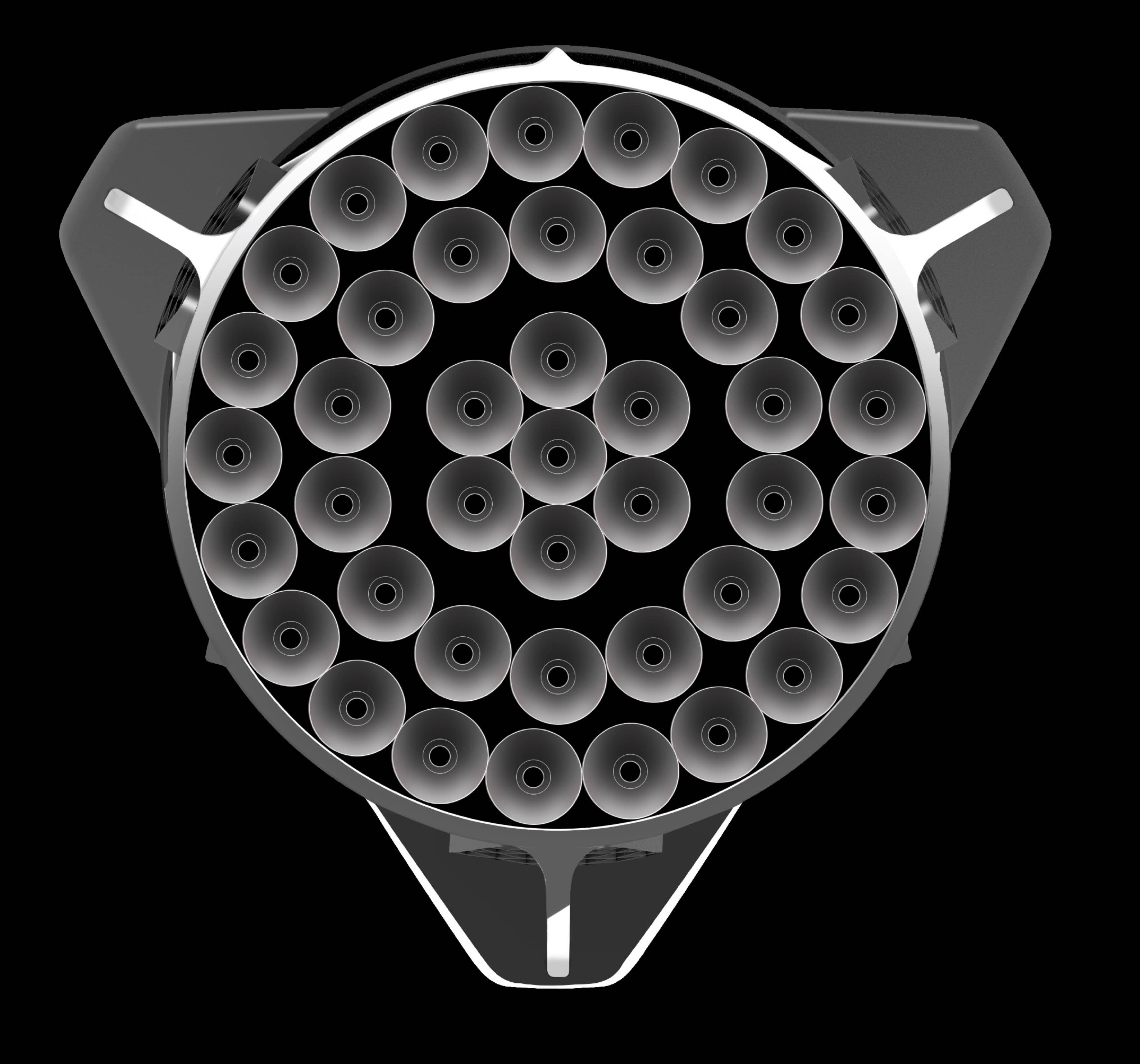

The Big Fucking Spaceship

So then there’s the spacecraft—which SpaceX calls the Interplanetary Spaceship, and which I’m going to keep calling the Big Fucking Spaceship because it’s more fun. The BFS is the big cool-looking thing on top of the BFB (in case you’re getting Big Fucking Confused—the Big Fucking Spaceship (BFS) on top of the Big Fucking Booster (BFB) together make what I’ve been calling the Big Fucking Rocket (BFR)). The BFS is what will take the people and cargo to Mars. It’s also what will launch, on its own, off Mars and return to Earth with people who want to come back.

The BFS is itself the size of a tall, 16-story building, and is 55 feet wide at its thickest point. In addition to hundreds, and eventually a thousand tons of cargo, the BFS will be able to carry as many as 100 people at the beginning, and Elon believes that number could grow to 200 and even above 300 people over time—like a cruise ship.

With nine Raptor engines, it’ll have more liftoff thrust on its own than any of today’s rockets—including next year’s Falcon Heavy. For a second-stage, cargo-carrying spacecraft to pack more thrust than even the most powerful first-stage rockets is outrageous.

Here’s a cross-section up close:

I asked Elon what it’ll be like to ride in it. He said, “Well, you’d be in a giant spaceship in microgravity.5 I mean, it would be pretty fun. You’d be floating around.”

Good point.

In the presentation Q&A, he added: “It has to be really fun and exciting, it can’t feel cramped or boring. The crew compartment is set up so that you can do zero-g games, you can float around, there will be movies, lecture halls, cabins, a restaurant—it’ll be really fun to go.”

Um, yeah, get me on that shit now. A zero gravity cruise ship. With this view:

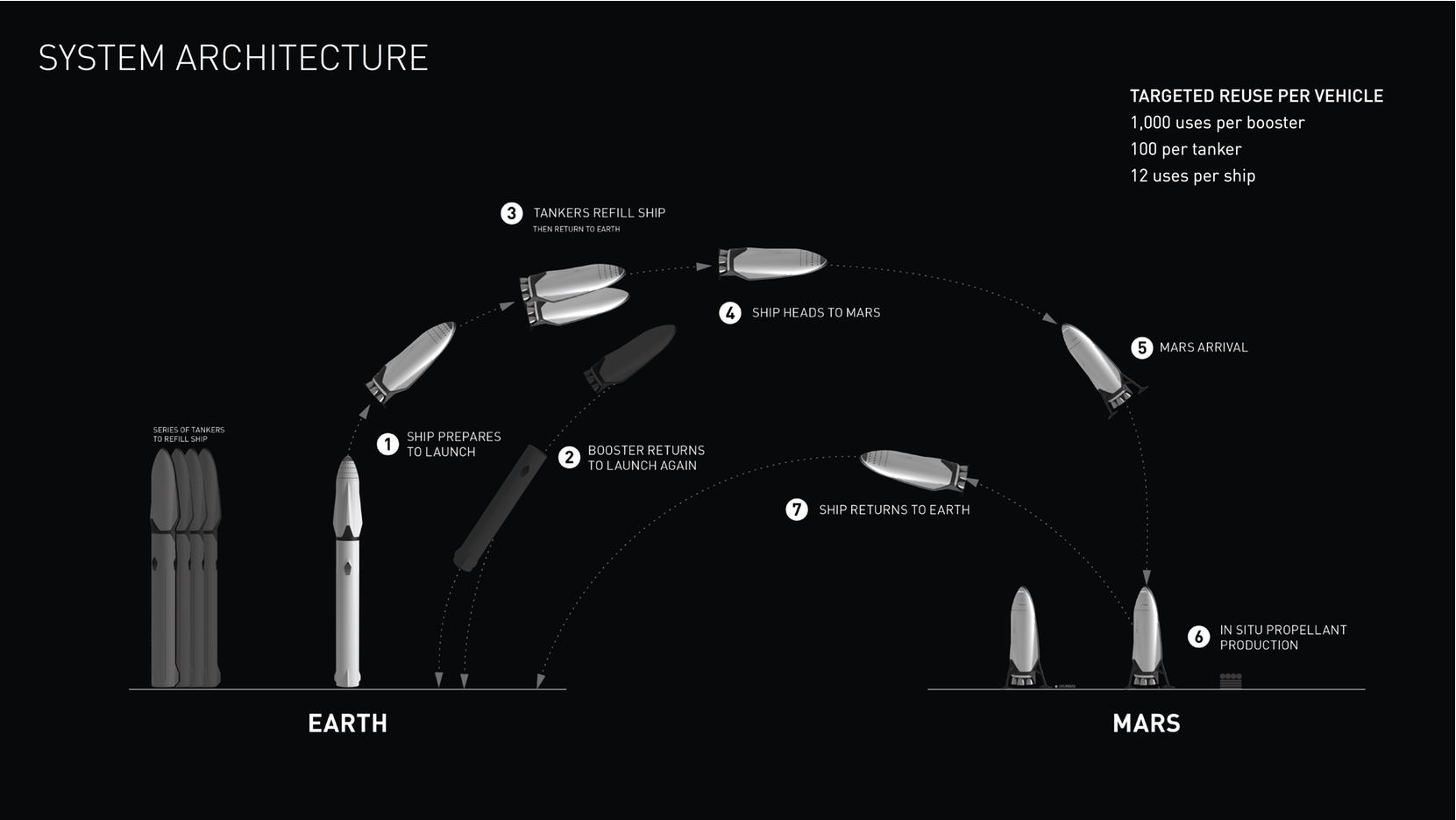

And if you were to go, here’s how the whole thing would work:

1) Get on the ship. The BFR will be taking off from pad 39A at Cape Canaveral, Florida—the same pad that the Apollo astronauts left from. This is because that pad was built to be absurdly large since they didn’t know yet how big a rocket they’d be using. When you get there, you head up the tower and across the bridge into the Big Fucking Spaceship.

2) Take off. You strap in, and the BFR lifts off. After a few minutes, the first-stage BFB separates and heads back down to Earth. The BFS that you’re in continues onward and settles into Earth’s orbit.

3) Refuel in orbit. After landing back on Earth, the BFB is capped with a new BFS—this one full of propellant (liquid oxygen and methane).6 It lifts off again and pings the propellant-filled spaceship into orbit, where it rendezvouses7 with your spaceship. The two connect like two orcas holding hands as the propellant is transferred.

This happens a few more times until your spaceship is entirely refueled.8 This process is critical A) for lowering the cost of the trip, and B) for making the trip much faster. People have always thought a journey to Mars would take six or nine months, but the BFS will get there in three.

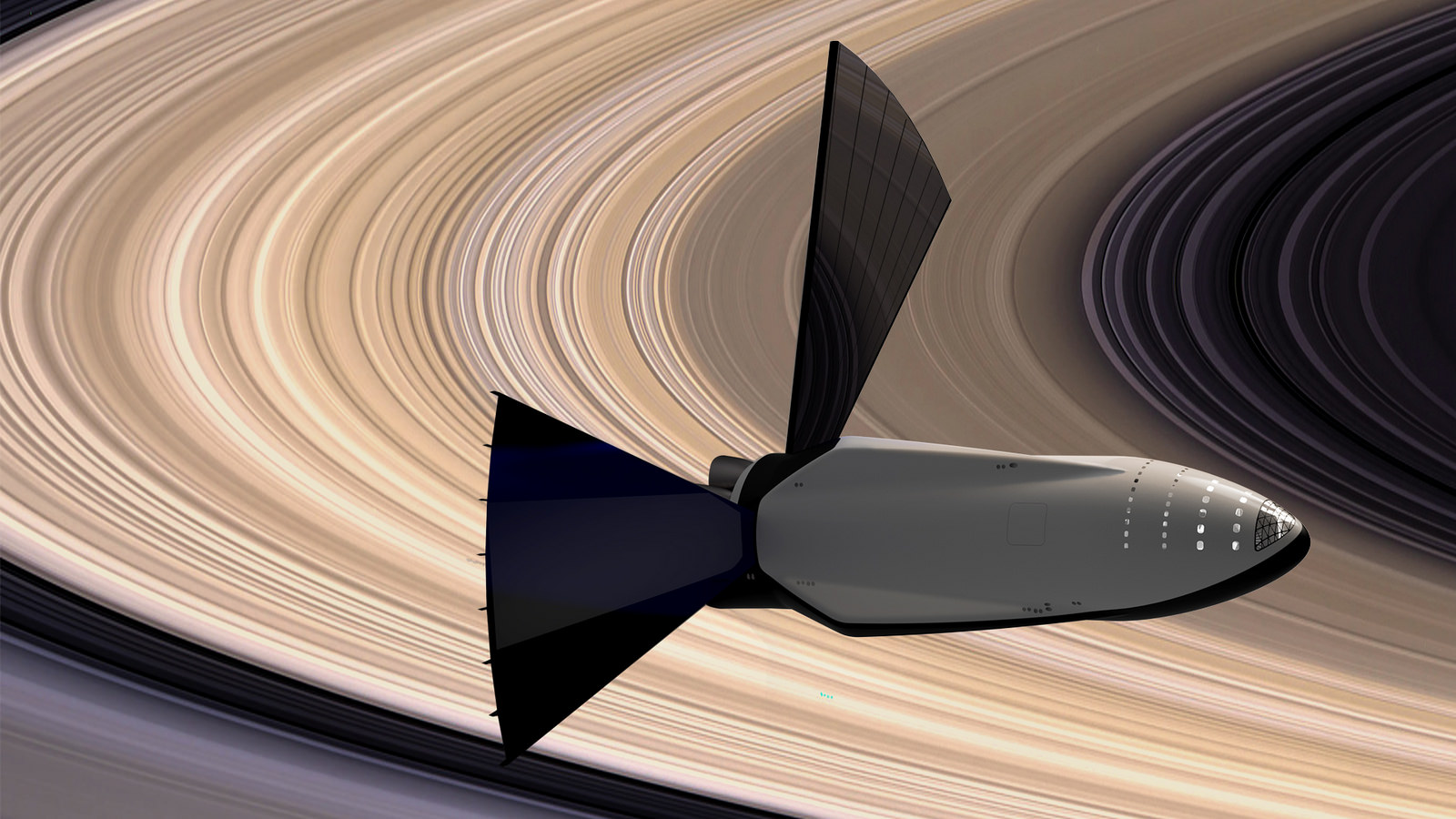

4) Head to Mars. Three months of fun times in microgravity and getting really sick of the other people on the ship.9 During the journey, the spaceship steers using cold gas thrusters, powered by huge solar arrays:

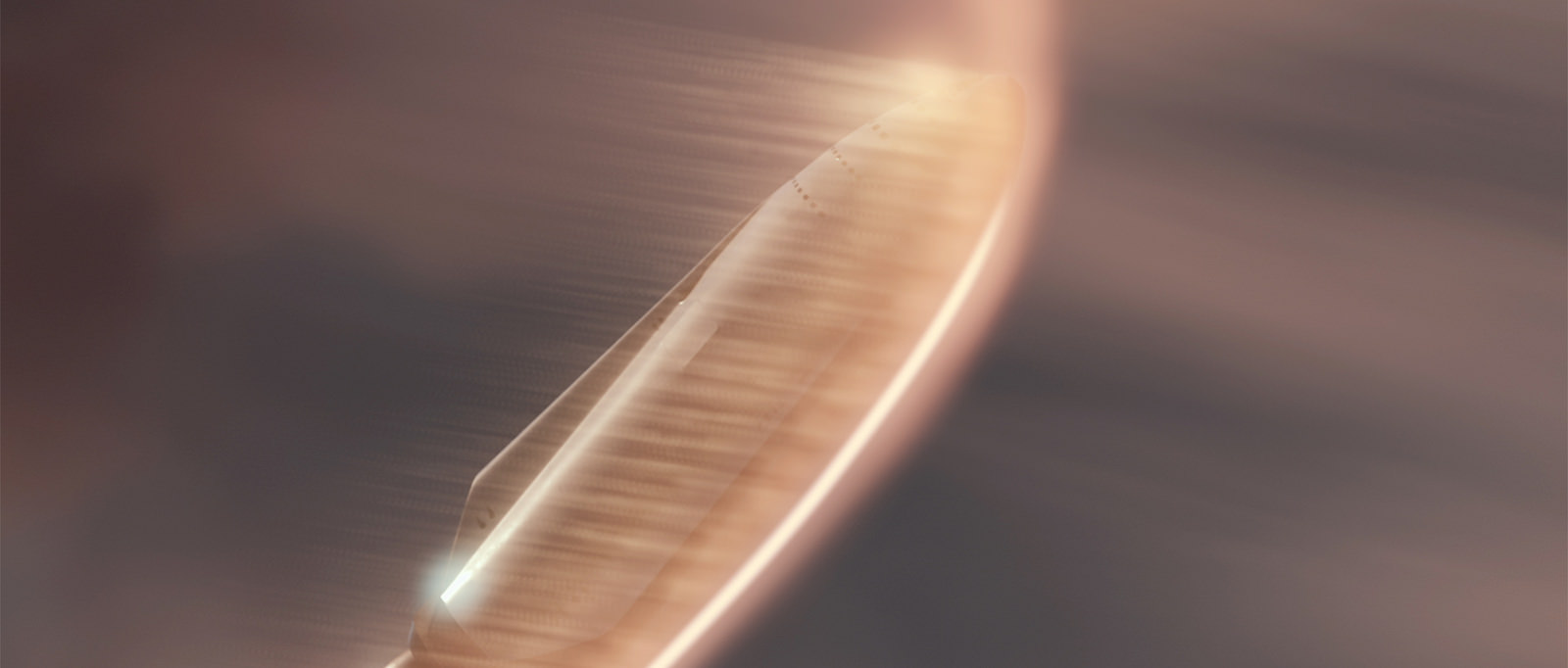

5) Enter the Mars atmosphere. Time for the heat shield to be in the shit:

6) Land on Mars. Upright, the same way the first stage lands on Earth.

7) Live on Mars for a while doing god knows what. If it’s early on in the colonization process, you’re probably there to work and help build up the initial industries. Later on, it could be anything—research, entrepreneurship, or just simply adventure.

8) Make propellant on Mars. This will be one of the key early industries to set up on Mars. Propellant consists of liquid oxygen (O2) and methane (CH4), which are both conveniently easy to make from the massive quantities of H2O (ice) and CO2 (the main gas in the Martian atmosphere) already sitting on Mars. They’ll use this propellant to load up the spaceship you came there on in preparation for its voyage back to Earth. Doing this spares the massive expense of having to carry propellant all the way from Earth for the return trip.

9) Either stay forever or come back. If you come back, you’ll do so by boarding one of the BFS’s that came over in the last batch.

10) Land vertically on Earth. Just like you did on Mars. The spaceship will go through routine maintenance in preparation to head back to Mars two years later.

11) Be that insufferable person who can’t be part of any conversation without figuring out some way to bring up your time on Mars.

Mission complete.

This kind-of-confusing diagram sums it up:

And this video sums it up very deliciously:

So that’s the deal with the Big Fucking Rocket and how it’ll all work.10

Now let’s talk about how this all might play out.

The Plan

Back to reality. So how do we get from, “there’s this rad potential rocket that might be ready to launch in five years” to “we’re a thriving multi-planetary civilization with a million people on Mars”?

10,000 flights. That’s how many BFS trips to Mars Elon thinks it’ll take to bring the Mars population to a million.

Why 10,000? Because there will be at least 100 people on most trips, and that number will go up over time—but there will also be some people coming back from Mars each time other people go. In the lower part of each BFS will be a huge cargo compartment. Elon thinks we’ll need to get at least 10 million tons of cargo to Mars for the million-person colony to become self-sustaining, which will happen in a little over 10,000 flights if SpaceX can get the cargo payload capacity up to 1,000 tons relatively quickly, as they hope to.

And when will these 10,000 trips start?

Well let’s take a look at the Mars-Earth Synodic calendar—which deals with the dates when Earth and Mars are closest to each other (called a “Mars opposition”). Earth’s orbit is smaller than Mars’s, so Earth goes around the sun quicker—so much so that every 26 months, Earth laps Mars and they’re briefly next to each other. That’s the one time when Earth-Mars transfers can happen.

We’re currently pretty close to Mars, since the last Mars opposition happened on May 22, 2016. That’s why, if you happen to be an “oh shit there’s a way-too-bright star let me take out my Sky Guide app and figure out which planet that is and then tell everyone I’m with and find that, yet again, no one cares, because everyone is a horrible person” nerd like me, you know that all summer, Mars has been super prominent and bright in our night sky.11 A year from now, Mars will be on the other side of the sun from us, and we won’t see it in our night sky at all.

The 2016 Earth-Mars opposition is also a special one, because it’s the last time it’ll happen without anybody talking about it.

Why? Because starting with the next one in July of 2018, SpaceX will start sending stuff to Mars each time there’s an opposition, and this will become increasingly big news each time. Here’s the tentative schedule, if everything goes perfectly to plan:

Upcoming Mars Oppositions – and what SpaceX is planning for each

July, 2018: Send a Dragon spacecraft (the Falcon 9’s SUV-size spacecraft) to Mars with cargo

October, 2020: Send multiple Dragons with more cargo

December, 2022: Maiden BFS voyage to Mars. Carrying only cargo. This is the spaceship Elon wants to call Heart of Gold.

January, 2025: First people-carrying BFS voyage to Mars.

Let’s all go back and read that last line again.

January, 2025: First people-carrying BFS voyage to Mars.

Did you catch that?

If things go to plan, the Neil Armstrong of Mars will touch down about eight years from now.

And zero people are talking about it.

But they will be. The hype will start a couple years from now when the Dragons make their Mars trips, and it’ll kick into high gear in 2022 when the Big Fucking Spaceship finally launches and heads to Mars and lands there. Everyone will be talking about this.

And the buzz will just accelerate from there as the first group of BFS astronauts are announced and become household names, admired for their bravery, because everyone will know there’s a reasonable chance something goes wrong and they don’t make it back alive. Then, in 2024 they’ll take off on a three-month trip that’ll be front-page news every day. When they land, everyone on Earth will be watching. It’ll be 1969 all over again.

This is a thing that’s happening.

Elon doesn’t like when people ask him about this first voyage and the Neil Armstrong of Mars. He says that it’s not about humanity putting a new multi-planetary feather in its cap, and he’s quick to point out, “putting people on the moon was super exciting—but where’s our moon base?” In other words, having humanity give Mars a high five for bragging rights is not what matters—what matters is carrying out the full vision of actually creating a full, self-sustaining civilization on Mars.

And yeah, sure, fine. But I’m excited for 2025. It’s gonna be so fun.

Anyway, so then the next Mars opposition will roll around in 2027. This time, if everything stays on track, multiple BFS’s will make the trek to Mars, carrying more people than were in the original group in 2025. And the spaceship that went over in 2025—the space Mayflower—will make its return trip to Earth, carrying some of the first group of Mars pioneers back home. They’ll return to massive celebration as international heroes, and the legendary spaceship will head off to enjoy its life in the Air and Space Museum.

Meanwhile, we’ll all be glued to the TV12 as the group of BFS’s arrive on Mars, where the people in them will continue the grueling work started by the 2025 group. The early colonists will have a hard job like early colonists always do—and this will be extra hard. Not only will they have to truly start from scratch—digging mines and quarries and refineries, constructing the first underground village habitat with the first Martian hospitals and schools and greenhouse farms, laying down a giant plumbing system to pump water into the village, building that first rocket propellant plant—but they’ll have to do all of this in a place where they can’t go outside without a spacesuit on, and where everyone and everything they’ve ever known is on a pale blue dot in the night sky.

It’ll be hard, but for the explorers of our world the payoff may be worth it. Elon says: “You can go anywhere on Earth in 24 hours. There’s no physical frontier on Earth anymore. Now, space is that frontier, so it’ll appeal to anyone with that exploratory spirit.”

In April of 2029, SpaceX will send an even larger group of spacecraft, people, and cargo to Mars. This time, it’ll probably get less attention. By 2029, we’ll probably be getting used to the idea that there are people on Mars and that every 26 months, a great two-way migration occurs.

The growing Mars colony will continue to entice the adventurers—those who read about the great sailing exhibitions of the 15th and 16th centuries and yearn to be there. When I asked Elon about how the small colony will grow and evolve, he said: “Think of the Mars colony as an organism that starts off as a zygote, and then becomes multi-cellular, and then gets organ differentiation—so it doesn’t look exactly the same all the way along, any more than the first settlement in Jamestown wasn’t representative of the United States today. It’ll be the same with Mars—Mars will be the new New World.”

The 2031 and 2033 and 2035 oppositions will bring substantially more people to the new New World. By this point, the budding Martian city will be a part of our lives. We’ll follow the Twitter feeds of some of our favorite journalists on Mars to keep up with what’s happening there. We’ll all get hooked on Mars’s first hit reality shows. And some of us will start thinking, “Should I sign up to go to Mars one of these years before I get too old?”

By 2050, there will be over a hundred thousand people on Mars. The company your son works for might have a branch there, and he’ll be saying goodbye to a couple co-workers who are about to head to the planet for a 52-month stint. He tells you that he doesn’t want to go because he doesn’t want to take his ninth-grade daughter away from her life and her friends. But he says she’s applying to a program that would bring her to Mars from the ages of 17 to 23 for an urban planning degree. You worry, even though you know it’s irrational. It’s just that you remember the days when going to Mars was risky and dangerous, and some part of you is still uncomfortable with it. And what if she decides not to come back?

By 2065, the early days of Mars seem primitive. During the first few Mars migrations, only a few spaceships made the trip with only 100 people in each, it was prohibitively expensive to go, it took three months to get there, and there were only a few very grueling industries on Mars to work in.

In 2065, every Mars opposition sees over 1,000 ships make the trip, each carrying over 500 people and a couple thousand tons of cargo. Half a million people make the journey every two years, and about 50,000 less than that come back, because Earth-to-Mars migration capacity grows a little bit each time as more ships are built. The trip, which now takes only 30 days, costs only $60,000 (in 2016 dollars)—and most people just pay off the ticket price with their well-paying job on Mars (labor is in high demand as the early Mars cities continue to expand and new cities are built).

Many people remember those early days of the Mars colony when it was all about SpaceX—funded by SpaceX or their cargo clients and driven by their ambition and their ingenuity and their guts. But now, dozens of companies specialize in Earth-Mars transit and hundreds of companies focus on development and entrepreneurship on Mars. And transit is paid for like planes and trains and buses are paid for today—by passengers buying tickets.

A decade later, the 2074 migration brings the Mars population above a million people. Small celebrations break out around both worlds, as a long-awaited landmark is achieved. Most people though, don’t even notice.

___________

Everything I just said was based on things Elon said on my phone call with him. Some of it was numbers he said directly—like the last paragraph, which came from him saying, “I’m hopeful that we can get to a million roughly 50 years after the start.” Other times it was me extrapolating a possible future, given the predictions I heard from him. It’s all based in reality. At least, it’s based in Elon Musk’s best crack at reality. He was very careful to qualify everything that sounded like a prediction or a projection with, “This is what might happen if things go well—but there’s no way to know, and many things could go wrong along the way.” He emphasized that “it’s not that SpaceX has all the answers and we’ve got it covered or anything like that—it’s that we want to show that it’s possible. But it’s far from a given.” As for things that could go wrong, he listed off a few (like World War III), and one of his biggest concerns is that if he somehow dies young, SpaceX could be taken over by someone who wants to milk the company for profit instead of staying single-mindedly focused on the Mars civilization mission.

But if SpaceX can manage to get this thing started, Elon thinks it could be not just a big deal in itself, it could jumpstart a slew of new possibilities for humanity. He explains:

The big picture isn’t just to back up the hard drive but to really change humanity into a multi-planetary species. Essentially what we’re saying is we’re establishing a regular cargo route to Mars. With the economic forcing function of interplanetary commerce, there will be the resources and the incentive to massively improve space transport technology, and I think then things really go to a whole new level.

What I’m describing may sound really crazy, but it actually will be a small fraction of what is ultimately done, as long as we become a two-planet civilization. Look at shipping technology in Europe. When all you had to do was cross the Mediterranean, the ships were pretty lame—they couldn’t cross the Atlantic. So commerce basically had short-range vessels. Without the forcing function, shipping technology didn’t improve that much—you could do the same things with ships, pretty much, around the time of Julius Caesar as you could around the time of Columbus. 1,500 years later, you could still just cross the Mediterranean. But as soon as there was a reason to cross the Atlantic, shipping technology improved dramatically. There needed to be the American colonies in order for that to happen.

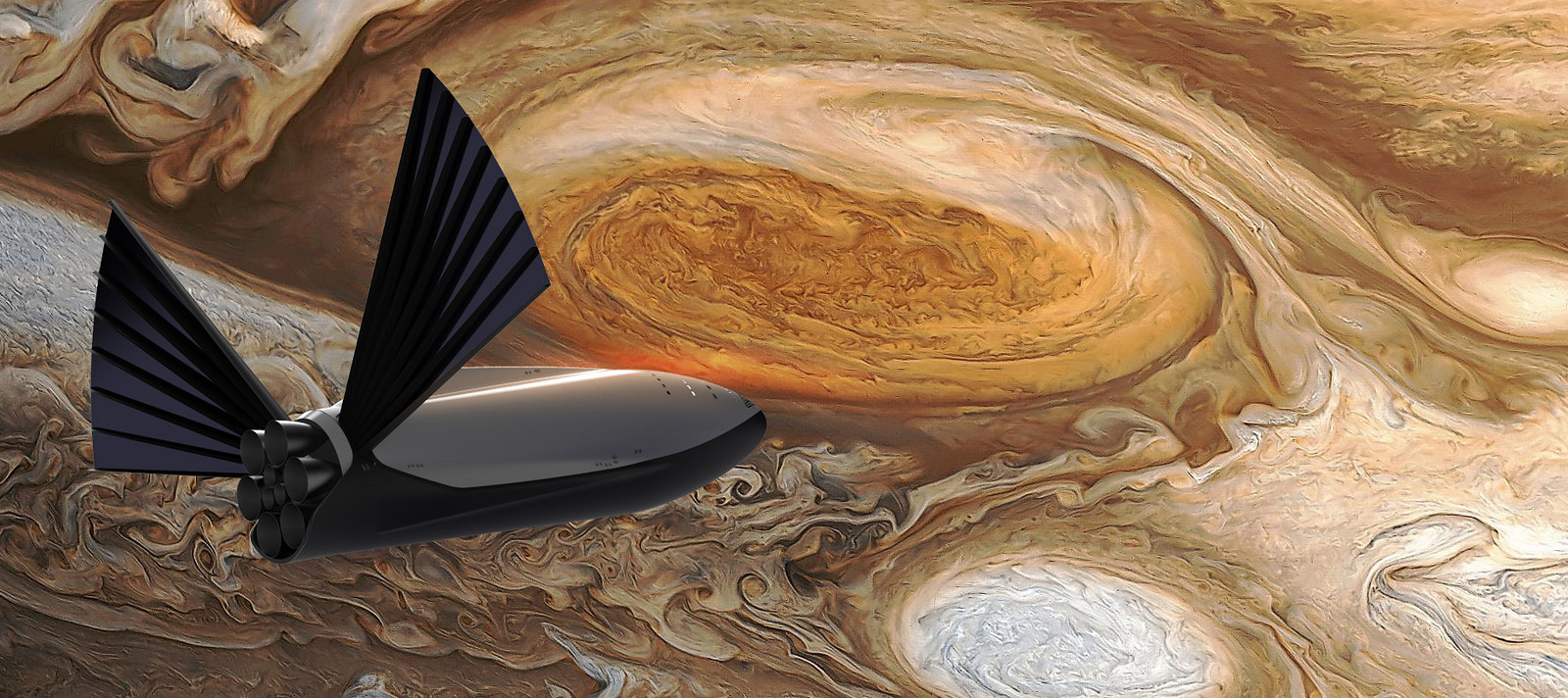

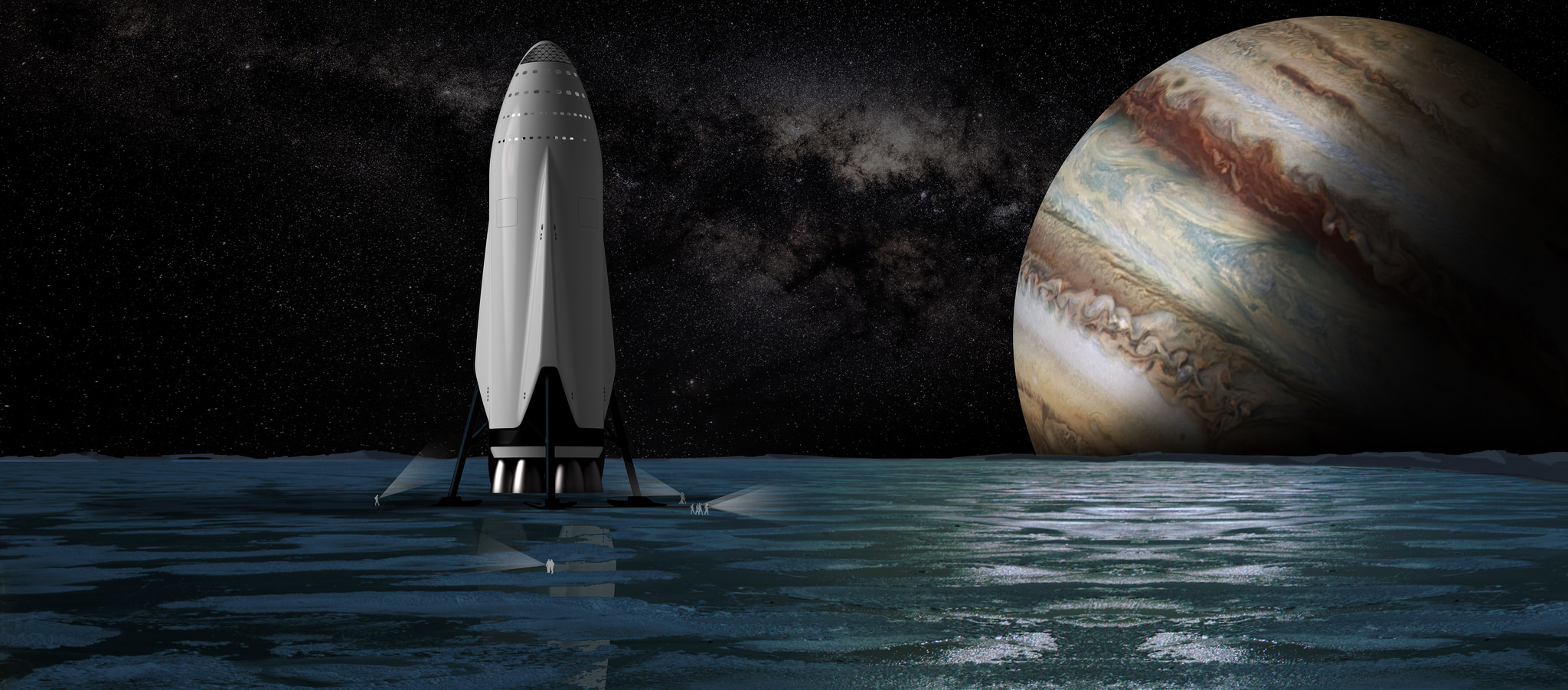

The people at SpaceX believe that once we’re on Mars, the rest of the Solar System becomes accessible as well. That’s why they didn’t just create images of their Big Fucking Rocket standing proudly on Mars. They showed it flying by Jupiter.

And Saturn.

And bringing human explorers to faraway moons.

They’re planning for a time when any person can go anywhere they want in our vast Solar System—a new golden age for exploration, with uncharted physical frontiers in every direction.

_______

If you like Wait But Why, sign up for our email list and we’ll send you new posts when they come out.

To support Wait But Why, visit our Patreon page.

_________

Here’s the whole WBW Elon Musk series:

Part 1, on Elon: Elon Musk Series: Introduction

Part 2, on Tesla: How Tesla Will Change the World

Part 3, on SpaceX: How (and Why) SpaceX Will Colonize Mars

Part 4, on the thing that makes Elon so effective: The Chef and the Cook: Musk’s Secret Sauce

Extra Post #1: The Deal With Solar City

Extra Post #2: The Deal With the Hyperloop

Six other Wait But Why explainers:

The American Presidents—Washington to Lincoln

From Muhammad to ISIS: Iraq’s Full Story

The AI Revolution: Road to Superintelligence

The Fermi Paradox: Where are all the aliens?

How Cryonics Works (and Why it Makes Sense)

This is a Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy reference. In the book, Heart of Gold was “the first spacecraft to make use of the Infinite Improbability.” Elon likes the name because he thinks SpaceX’s path was highly improbable.↩

To be clear, payload is what the rocket can actually bring to space. Thrust is what the engines can push to space, which has to include both the entire BFR and its contained payload. Almost all of a rocket’s thrust is used to lift the rocket itself, with only a small fraction of it allotted for the payload. When I talk about thrust in these posts and say how many cars a set of engines could push to space, I’m talking about a hypothetical scenario in which there is no rocket, just the rocket’s engines with a platform on top of them and cars stacked on top of the platform.↩

Here’s a video of Raptor’s first test firing, which happened a few days ago. It would be so unfun to put your hand through that column of flame.↩

I asked Elon why there were 42 smaller-sized engines instead of a smaller number of huge ones, and he said that they had imagined larger engines at one point but that “optimization seems to call for more small engines, not fewer big engines.” I can’t explain more than that because I don’t get it.↩

We often think of floating astronauts as being in “zero gravity.” In fact, they’re very much inside of the Earth’s gravity well when they’re floating—they’re just orbiting around the Earth so fast that they’re in constant free fall. The effect is the same—they float—but since they’re not actually in zero gravity, we call it microgravity.↩

The methane part of that is a big innovation. Other rockets, including the Falcons, use kerosene as the primary fuel—but for a bunch of reasons, methane seems to make more sense for a Mars trip.↩

Upsettingly-spelled word.↩

Elon says that this is the plan if the refueling process is quick, like a couple weeks or less. If it takes a lot longer, then the spacecraft will be launched first without people, and then whenever it’s all refueled and ready to go, a spacecraft carrying just people will be launched and it will deliver the crew to the spacecraft for an Earth orbit rendezvous.↩

People like to bring up the dangers of space radiation during this time. Elon thinks the dangers are overstated, and that with proper precautions (like a protective layer of water around the crew cabin), the radiation harm to a crew member would be similar to the damage to your body if you were to become a smoker during those three months and then stop. Not ideal, but not too big a deal.↩

In the presentation, Elon went off on a tangent at one point that delighted me. He talked about the possibility of the BFR’s spaceship doubling as a super-fast way to transport stuff or people around the Earth: “It actually has enough capability that you could maybe even go to orbit with the spaceship…and maybe there is some market for really fast transport of stuff around the world…We could transport cargo to anywhere on Earth in 45 minutes at the longest—most would be maybe 20, 25 minutes. So maybe if we had a floating platform off the coast of New York, you could go from New York to Tokyo in 25 minutes. You could cross the Atlantic in 10 minutes. Most of your time would be getting to the ship, and then it would be real quick after that. There are some intriguing possibilities there, but we’re not counting on that.” YES. Amazing glimpse of the world of the future, when someone will text you from Delhi and ask if you want to zip over from San Francisco to grab lunch, and you’ll say, “Sure, but I have a meeting in two hours, so I can’t stay long.” Except you won’t, because you’ll just meet your friend virtually and it’ll feel exactly how it would to be there in person. So there goes that.↩

Right next to Mars all summer has been a pretty bright Saturn—something I’ve also told a bunch of people who don’t care.↩

or whatever 2027 humans are glued to when they’re glued to something↩

All images are from spacex.com, unless they have “waitbutwhy.com” written at the bottom, in which case they were made by me.↩